Seeing that ENS is struggling with governance, I think it's time to talk about the DAO's issues.

When market conditions turn unfavorable, pre-existing issues often become magnified and eventually come to light. Recently, Aave and ENS have each exposed internal organizational challenges, all of which ultimately point to the DAO model at their core.

After years of development, it is now evident that while DAOs have achieved decentralization, they still face every management issue that plagues centralized organizations.

What happened?

The recent internal disputes within Aave and ENS have been widely discussed. For those unfamiliar, here is a brief overview of the key events.

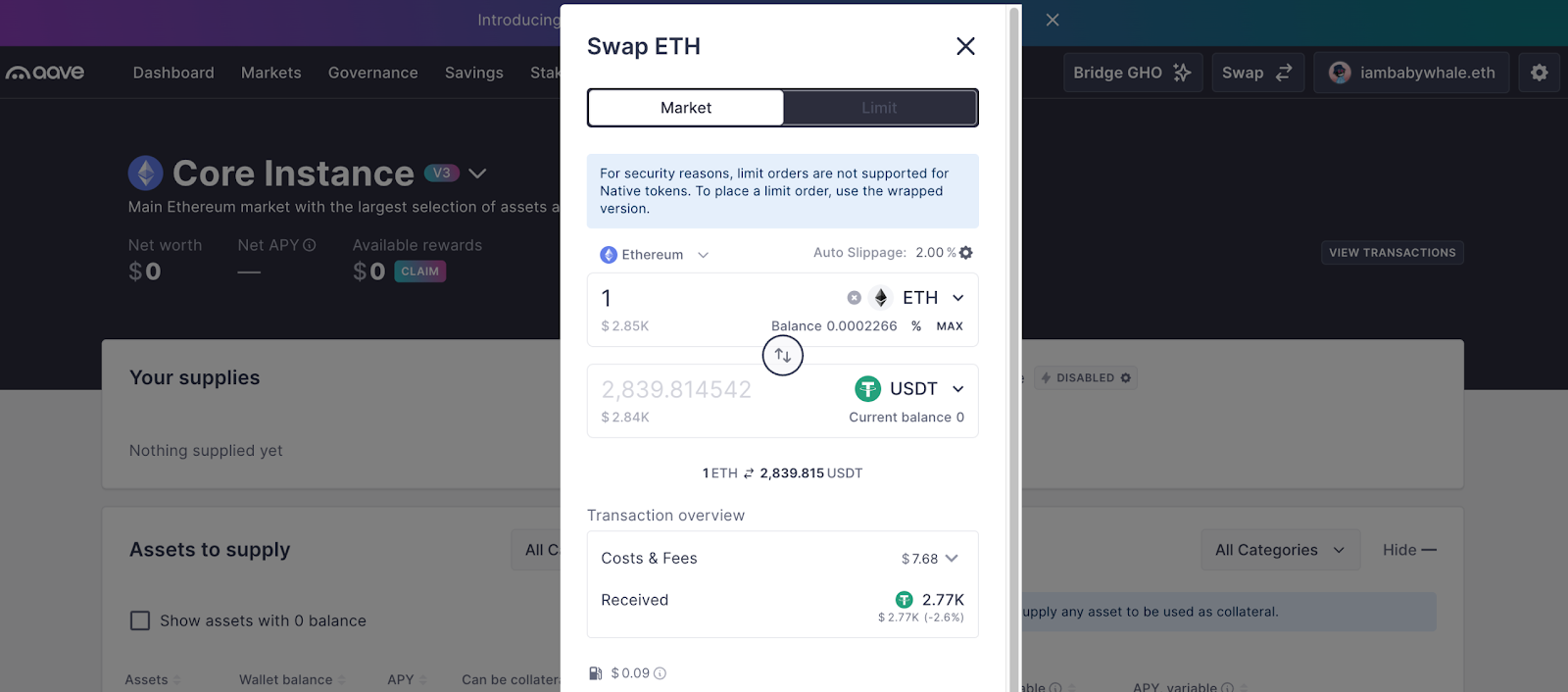

Let’s start with Aave. The conflict involves Aave Labs and Aave DAO. Previously, Aave Labs replaced ParaSwap with CoW Swap on the front end, redirecting related fees from the DAO to an address controlled by Aave Labs.

As a result, Aave DAO accused Aave Labs of privatizing protocol revenue. Aave Labs countered that transaction fees pertain to the front end and product layer, not the protocol itself, and that operating the front end incurs costs, making it reasonable to retain this income.

Within Aave’s architecture, the DAO controls the protocol, including contract upgrades and treasury management. All protocol development or upgrade proposals require DAO approval through voting before implementation. Aave Labs serves as the core development team and also drives product, marketing, and other project growth initiatives.

In summary, Aave Labs developed the protocol and, after issuing tokens, transferred ownership to the DAO. If Aave Labs needs funding for development, operations, or marketing, it must apply to the DAO. Without DAO approval, Aave Labs cannot access those funds.

From Aave Labs’ perspective, the DAO has not “found its place.” Without the dedication and strategic insight of certain Aave Labs members, Aave would not exist as it does today. The implication is that the ability to vote with AAVE tokens exists only because Aave Labs created the protocol, so the DAO should not overstate its own significance.

From the DAO’s perspective, while Aave Labs may have had a “god’s eye view” in the early days, subsequent initiatives—such as Lens and even version 4—consumed substantial treasury funds without delivering proportional returns. Some have also noted that Aave Labs repeatedly tried to leverage the DAO for its own objectives but was exposed each time.

This conflict between founding contributors and the current management system represents an external dispute for the DAO. ENS, in contrast, is facing internal DAO strife.

Last month, ENS founder Nick Johnson posted a pointed message on the forum, noting that the DAO is now rife with political infighting, capable individuals are leaving, and leadership is falling to those lacking experience or whose interests do not align with the protocol.

This message was likely prompted by a proposal from ENS DAO Secretary Limes, recommending the termination of three working groups—Meta-Governance, Ecosystem, and Public Goods—at the end of the sixth term, December 31, 2024. The reasons: first, proposals have devolved into a “you support me, I support you” dynamic, with little focus on substantive work; second, the lack of admission standards has led to “bad money driving out good.” Limes argued that process improvements cannot solve these structural problems and that shutting down is the only viable solution.

Current DAOs Are a Step Backward

To date, the most successful DAO is the Bitcoin community, with Ethereum perhaps a distant second. Why is DAO governance so often inefficient and fraught with issues? As someone who has consistently opposed pure democratic voting DAOs, I offer several observations for consideration.

First, the foundational premise for creating a DAO is fundamentally flawed.

Blockchain and cryptocurrency emerged to counter centralized authority, based on the belief that concentrated power leads to unfair decisions. Whether decentralization is seen as a Web3 standard or centralization is blamed for opacity and corruption, the argument remains: “centralization” is the root of all problems.

In practice, the same issues found in traditional organizations are equally prevalent—and often more damaging—in DAOs. Launching a DAO simply because centralization is deemed “backward” misses the real core of the problem.

With a background in management science, I’ve learned that management does not distinguish between centralization and decentralization. Its essence is captured by four concepts: planning, organizing, leading, and controlling. While I appreciate the idea of decentralization, the term “DAO” reveals a lack of understanding of management science and a disregard for historical precedent.

Management science has never judged centralization or decentralization as inherently good or bad, but instead seeks the most effective approach. For any given problem, if centralization works, use it; if decentralization is better, choose that. Organizational evolution is a process of natural selection. Current mainstream structures suggest that DAOs—often touted as superior in Web3—may actually be outdated. Their “revival” could simply reflect wishful thinking among industry veterans.

Management science is about understanding human nature. DAOs have not changed people, the greatest variable in management, and attempts to use democratic decision-making ultimately amplify the worst aspects of human nature.

In June 2024, Yuga Labs CEO Greg Solano proposed dissolving ApeCoin DAO and transferring all assets and responsibilities to a new Yuga Labs entity, ApeCo. The stated goal was to focus resources on ApeChain, Bored Ape Yacht Club, and Otherside. The proposal passed by vote. What struck me most is that ApeCoin DAO often sees absurd proposals.

Interested readers can browse Snapshot themselves. Proposals such as developing new games, launching standalone NFT marketplaces, or creating meme tools—all difficult and unrewarding—were approved one after another. Shutting down the DAO and returning authority to the core team may be controversial, but under current circumstances, it is the best available option.

The disputes and challenges faced by Aave and ENS are common in traditional companies: veteran employees resisting new systems, and organizations prioritizing error avoidance at the expense of innovation. Companies at least have selection and elimination mechanisms, whereas open DAOs almost inevitably suffer from “bad money driving out good,” with no corrective systems to address these issues. Talented individuals can earn competitive salaries at companies or start their own ventures. Why would they work for countless anonymous investors on projects with uncertain outcomes and little reward?

Among the leading, long-standing projects with broad market recognition, none have succeeded because of DAO decision-making. In almost every case, the core team or investors set the direction, and the DAO merely provides a formal vote.

Before a project matures, this is the only viable approach. The core team’s expertise and insight far exceed those of most token holders, and they understand the project in depth. They are best positioned to make early decisions. There are countless examples of democracy gone awry, such as British citizens Googling “Brexit” after voting, or Ukraine electing a comedian as president.

“A company needs one person with the final say” has become a widely accepted principle. This does not mean such systems are immune to mistakes, but they allow for timely course correction. If every decision requires exhaustive discussion and consensus, it leads only to endless disputes and paralysis. DeFi pioneer AC once noted that people questioned his decisions and tried alternative approaches, only to realize in the end why his seemingly unreasonable choices were justified.

The second issue is the ambiguous role of DAOs in the ecosystem.

DAOs are, in my view, a highly distorted construct. Their authority is limited to voting, while ownership of protocol code, brand, and technology remains outside the DAO. As token holders, we can participate in governance, but we do not actually own the protocol.

The logic that public blockchain tokens serve as ecosystem currencies is sound, but what about DApp tokens? Global regulations currently define tokens as a new asset class, not as securities, but their precise asset nature remains undefined.

This asset type—granting governance rights without ownership—becomes extremely precarious when problems arise. For example, if a DAO-approved expenditure leads to corruption or unclear fund allocation, who is accountable? Should responsibility fall on token holders who voted in favor, the executors, or the protocol developers? Everyone on this chain bears some responsibility, yet there is no clear basis for accountability.

Corporate structures, with legal entities, shareholders, and executives, are designed to ensure clear accountability in case of disputes. DAO governance is extremely vague on this point. In the ENS case, when proposals serve private interests or mutual support, there is no one to hold accountable because every step follows the governance process and every voter could be considered an “accomplice.”

I do not reject the DAO concept itself. Rather, with our deep management science knowledge and extensive historical precedent, decentralized governance could be made more efficient and rational. Yet most projects rely on “absolute democracy” to manage organizations worth billions, a practice that ignores sound principles and feels more like regression than progress.

Specific improvements must be tailored to each DAO. In Aave’s case, the key is balancing the relationship between Aave Labs and the DAO. For ENS, the priority is streamlining the DAO, retaining talent, and implementing a system that balances penalties and incentives to keep the right people engaged.

What’s interesting is that I do not believe these visionary founders are unaware of the issues with DAOs. Perhaps they simply refuse to accept them, believing they can succeed where others failed. In the end, history’s preference for the corporate model has its reasons. For the Web3 industry, only by experiencing these failures can we learn what works.

Statement:

- This article is republished from [Foresight News]. Copyright belongs to the original author [Eric, Foresight News]. If you have any concerns about this republication, please contact the Gate Learn team. The team will address your request promptly according to established procedures.

- Disclaimer: The views and opinions expressed in this article are solely those of the author and do not constitute investment advice.

- Other language versions are translated by the Gate Learn team. Do not copy, distribute, or plagiarize translated articles without referencing Gate.

Related Articles

What Is Solana?

An Introduction to ERC-20 Tokens

What is Onyx Protocol? All You Need to Know About XCN

What Are Smart Contracts?

What is USDC?